By Irene Stoel

Two years after ATA63 in Los Angeles, the Dutch Language Division was once again allowed to propose a Distinguished Speaker for the conference in Portland, Oregon. Frans Kooymans was recommended by one of our former Distinguished Speakers, Tony Parr (ATA60) because of his translation of “All God’s Dangers.” Recaps of Frans’ presentations at ATA65 will be published in two separate blog posts.

Frans Kooymans was born in the Netherlands and between the ages of 13 and 29 he lived in the United States (Florida to be exact), where he went to high school, first studied philosophy and theology at a seminary and then accounting at Florida State University. After coming back to the Netherlands, Frans worked in the financial sector, until he made a career switch at the age of 53. When Covid hit the world in 2020, Frans started his biggest challenge as a translator, deciding to translate “All God’s Dangers” written by Theodore Rosengarten.

Frans had bought the book in the spring of 1975 about 6 months after it was published. He had read it at the time, but then it sat on a shelf in his bookcase for more than 40 years. He picked it up to re-read it, and felt that the story of a black cotton farmer in Alabama in the early 20th century deserved to be known in the Netherlands too, as he saw similarities with the Dutch history of slavery in former colony Suriname. There are many publications in the Netherlands about this topic, with “De Doorsons” by Roline Redmond being one of them.

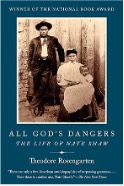

Theodore (Ted) Rosengarten was a student at Harvard in the fall of 1969, when he drove down to Alabama to interview Ned Cobb (Nate Shaw in the book) about the Alabama Sharecroppers Union. Ned/Nate was 84 years old at the time. He was a cotton farmer and the son of freed slaves. Ted got his PhD with his dissertation on Ned and later developed it into a book. The 560-page book was published about a year after Ned passed away and sold around 270,000 copies. Only one picture exists of Ned, with his wife and child, taken when he was 21 years old by an ambulant photographer. This is the picture we see on the cover of Ted’s book.

Theodore (Ted) Rosengarten was a student at Harvard in the fall of 1969, when he drove down to Alabama to interview Ned Cobb (Nate Shaw in the book) about the Alabama Sharecroppers Union. Ned/Nate was 84 years old at the time. He was a cotton farmer and the son of freed slaves. Ted got his PhD with his dissertation on Ned and later developed it into a book. The 560-page book was published about a year after Ned passed away and sold around 270,000 copies. Only one picture exists of Ned, with his wife and child, taken when he was 21 years old by an ambulant photographer. This is the picture we see on the cover of Ted’s book.

Frans did not have a publisher for his project and started the translation on his own initiative. His first question was: “Was Rosengarten still alive?” He discovered that Ted lived in South Carolina, found an email address and sent a message to introduce himself. Ted was thrilled about the idea for a Dutch translation. The book had only been translated into Hungarian and Chinese. Frans and Ted met and became friends, with Rosengarten writing an addendum to the original preface for the Dutch edition and even coming to Frans’s presentation at ATA65!

The book is divided into 4 parts: Youth, Deeds, Prison and Revelation. The first part is relatively short, about 94 pages, and can be seen as Shaw justifying his stories. “Deeds” (‘Daden’) is a recollection of Shaw by year. He knew numbers, but didn’t read or write. He gradually became self-sufficient and was despised by his neighbors because of his success. God’s danger, as explained in this part of the book, is actually the “boll weevil,” a species of beetle that feeds on cotton buds and flowers. He gets into a fight with a police officer and gets sentenced to 12 years in prison. While Nate was in prison, his wife and son managed the farm. The last part “Revelation” (‘Openbaring’) tells about Nate’s life after he’s released from prison. There were insurmountable barriers to go back to his old life. Many people he knew moved away while he was incarcerated and upon his return he discovered that the tractor had become an important machine on the farm.

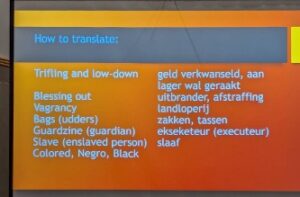

Some of the translation challenges were caused by the fact that the story is written as it is told, among other things with inflections that are typical of black people. Frans decided to translate this into spoken Dutch with colloquialisms. A literal translation of the title would not have been a good fit. Even though Nate is a religious man, it is not a spiritual book and the title could have taken away from the actual story. Frans decided on “De Kleur van Katoen” (“The color of cotton”) instead. Ted Rosengarten was incredibly helpful to Frans in explaining some of the expressions that Shaw uses in the book. Below are some more examples of the challenges Frans encountered while translating “All God’s Dangers.”

Nowadays Dutch tends to use “tot slaaf gemaakte” rather than “slaaf,” but Frans kept the latter to adhere to the historical context. Furthermore, there is the sensitivity about the usage of “black,” “negro” and “colored people.” Frans mostly used “zwarte,” because “neger,” the literal translation of “negro,” has a negative connotation to it. The word “nigger” was left in English. Some grammatical errors were also kept to stay authentic.

Frans was offered a royalty agreement to publish his book, but felt that this was a bad idea since this is a niche product and would most likely not be a bestseller. Many American books are not even translated into Dutch, with people more inclined to read the original in English. In the case of this book though, the southern diction and local expressions could be seen as an impediment. With the help of Ted Rosengarten and his publisher, Frans got in touch with ISVW Uitgevers (“Internationale School voor Wijsbegeerte”) and 1,000 copies of the book were printed in 2022.

Additional reading material about Theordore Rosengarten, Frans Kooymans and Nate Shaw:

The John Adams Institute – Nate Shaw and the Arc of History

NRC Handelsblad – Interview with Frans Kooymans and Theodore Rosengarten (in Dutch)

“De Kleur van Katoen” is available for purchase on bol.com