Hello, everyone! For this installment of the Resource Roundup series, we are looking at Shonagon (少納言), an online corpus of contemporary written Japanese maintained by the National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics (NINJAL, 国立国語研究所).

Hello, everyone! For this installment of the Resource Roundup series, we are looking at Shonagon (少納言), an online corpus of contemporary written Japanese maintained by the National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics (NINJAL, 国立国語研究所).

Why I find this resource useful

For anyone unfamiliar with corpora, they are collections of written texts used by linguists to analyze and investigate language. I think of corpora as a purpose-built database of language. For example, I have created a corpus using railway-specific patent abstracts to identify terms unique to the rail industry for inclusion in WIPO’s multilingual terminology portal, Pearl. At work, I have been building customer-specific corpora to guide my terminology and stylistic translatorial choices. I have referenced the Corpus of Contemporary American English to ensure my into-English translation does not suffer from undue Japanese influence. And I have referenced Shonagon to check how Japanese terms are used in context and particle collocations. Corpora can be excellent tools to check language for specific purposes, to prepare for interpreting assignments in specific domains, to check for linguistic anachronisms, and more.

How to use Shonagon

First, let’s get familiar with Shonagon’s search features. The search page has a simple set up. Your search field, 検索文字例, is at the very top followed by the 検索 and クリア buttons. There is also a link to include the context before/after your target search term or phrase (more on this later.)

First, let’s get familiar with Shonagon’s search features. The search page has a simple set up. Your search field, 検索文字例, is at the very top followed by the 検索 and クリア buttons. There is also a link to include the context before/after your target search term or phrase (more on this later.)

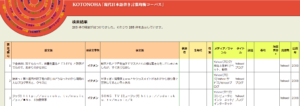

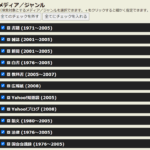

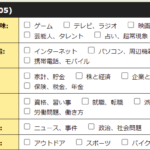

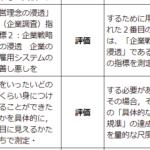

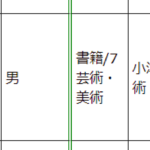

Under the query section is a list for メディア/ジャンル. These can be used to refine/restrict your search. You can search books, magazines, newspapers, white papers, textbooks, PR releases, Yahoo!知恵袋, Yahoo! Blogs, poetry, laws, and Diet proceedings (see first screenshot below).

- メディア・ジャンル

- Yahoo!知恵袋 categories expanded

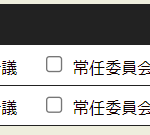

- 国会会議録 categories expanded

Each of these categories can be further refined. For example, the Yahoo!知恵袋 selection can be refined to entertainment/games or jobs or sports. 国会会議録 can be refined to 本会議, 常任委員会、特別委員会、and その他 for both houses (see second and third screenshots above).

Probably the easiest way to search is to enter your query into the 検索文字例 field at the top. Any hits that match your query will appear on the next page. In my experience, it takes a few seconds for the results to pop up, so don’t be worried if you don’t immediately see a list of returns after you click 検索. I find quick searches like this super useful when I’m translating into Japanese and want to check particle usage and conjugations. But sometimes a translator’s needs are more niche. For example, if you are translating an article about pop culture, you may not care what hits your query would have in the 国会会議録. Or if you are translating a novel set in the 1980s, you may want to exclude anything from the 1990s onwards to avoid linguistic anachronisms.

Using Shonagon: Example 1

By way of example, I looked up イケメン (attractive man, hottie).

By way of example, I looked up イケメン (attractive man, hottie).

Here are the query results for イケメン with all periods selected as searchable. Though it’s not shown in this screenshot, the earliest instance of イケメン is from 2001, which accounts for 2 of the 285 hits. Most hits were from 2005–2008. All 285 hits in the corpus came from 2001–2008. A translator may then think twice about using this term for source material that predates 2001.

Using Shonagon: Example 2

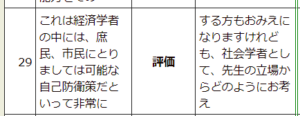

Let’s look at another example: parsing NHK public opinion polls about politicians. As someone who learned Japanese in school, I sometimes encounter familiar words used in ways that do not make sense to me contextually. Take 評価 for example. For the longest time, I only knew this word in the sense of the neutral act “to evaluate” or, in accounting, “to valuate.” So when I heard NHK talking about opinion polls where the respondents answered with either 評価する or 評価しない, I realized my basic understanding was insufficient. Based on context, it was clear that 評価する also has an intrinsic positive meaning and 評価しない has a negative one. That understanding can be checked in a corpus like Shonagon.

Let’s look at another example: parsing NHK public opinion polls about politicians. As someone who learned Japanese in school, I sometimes encounter familiar words used in ways that do not make sense to me contextually. Take 評価 for example. For the longest time, I only knew this word in the sense of the neutral act “to evaluate” or, in accounting, “to valuate.” So when I heard NHK talking about opinion polls where the respondents answered with either 評価する or 評価しない, I realized my basic understanding was insufficient. Based on context, it was clear that 評価する also has an intrinsic positive meaning and 評価しない has a negative one. That understanding can be checked in a corpus like Shonagon.

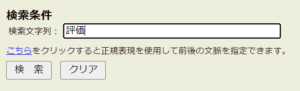

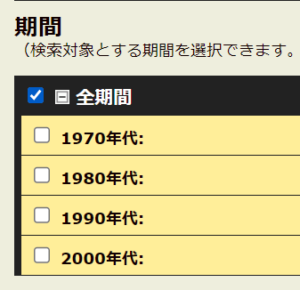

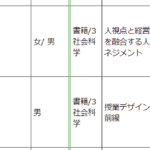

I did a basic search for 評価 using the media/genre and timeframes shown below.

I did a basic search for 評価 using the media/genre and timeframes shown below.

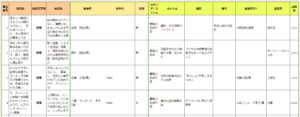

The basic search returns more than 1,000 hits; the first four are shown below.

The bulk of the hits match the “to evaluate” meaning of 評価, as demonstrated in the following excerpts (click for larger screenshot).

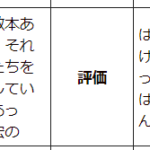

Before long, I did find matches for the new (to me) meaning of “approve of.”

But if looking for a needle in a haystack is not your thing, that’s where the 前文脈 and 後文脈 feature can help narrow down results. You may enter whole sentences in these fields, but in my experience that is too limiting to be useful. My sample source text mentioned 世論調査. However, entering that into the 前文脈 did not yield any results. Since my query term is often used in conjunction with 評価しない as two options in a poll, I entered that in the 後文脈 field (shown in the screenshot). That resulted in two hits, the content of which confirmed this new (to me) understanding of 評価 (shown in the following screenshot).

But if looking for a needle in a haystack is not your thing, that’s where the 前文脈 and 後文脈 feature can help narrow down results. You may enter whole sentences in these fields, but in my experience that is too limiting to be useful. My sample source text mentioned 世論調査. However, entering that into the 前文脈 did not yield any results. Since my query term is often used in conjunction with 評価しない as two options in a poll, I entered that in the 後文脈 field (shown in the screenshot). That resulted in two hits, the content of which confirmed this new (to me) understanding of 評価 (shown in the following screenshot).

Demerits of Shonagon

As endlessly fascinating as corpora are, they’re not perfect. As noted above, it takes Shonagon a few seconds to respond to your query. Shonagon’s content is beautifully organized and easy to read, but also painfully static. You cannot manipulate the Key Word In Context (KWIC) display (basically the orange columns in the screenshots above). The columns cannot be filtered by year or author or what comes before or after your key word. Finally, the resource is also static. While the dates differ depending on the material, there is nothing older than 1976 and nothing newer than 2008. Despite these limitations, I think Shonagon can be an excellent resource for Japanese–English linguists.

By: Audra Lincoln

Edited by: Syra Morii

Leave a Reply