Note: the below information is up-to-date as of September 28, 2020.

As legal translators, it is our mission to keep abreast of important court decisions to better understand the materials we translate. This time, the Court of Justice of the European Union (the “Court”) gave a preliminary ruling on July 16, 2020, in the field of data protection which directly impacts the way we and our U.S. clients do business with the European Union (“EU”). The article below summarizes the current law requirements, the preliminary ruling, and looks at the steps we can take to prepare for the future. You can find the complete judgement here and the official press release here. Click on the links for background information, if you’d like to learn more.

The Current Data Protection Legal Landscape

Since Regulation (EU) 2016/679 (“GDPR”) became applicable on May 25, 2018, processing of personal data concerning individuals living in the EU has become even more regulated than before. GDPR also applies to non-European Economic Area (the “EEA”) entities which process personal data related to individuals living in the EEA. Violations of requirements applicable to transfers of EU personal data from the EU to third countries are subject to the highest fines under the GDPR. Until today, U.S. entities doing business with the EEA relied mostly on two legal instruments to legally import EU individuals’ personal data into the United States:

- The so-called Privacy Shield to which more than 5,300+ U.S. businesses self-certified. This framework became an official adequacy decision through Decision 2016/1250. It was designed by the U.S. Department of Commerce and the European Commission and allowed both U.S. and European companies to legitimately transfer personal data from the EU to the U.S.

- The so-called European Commission’s Standard Contractual Clauses (“SCCs”) that you may have signed as an addendum to your translation services agreements with European translation agencies or other EU clients. The SCCs are defined in Article 46(1)(c) of GDPR and are used to legitimatize transfers of personal data from the EU to third countries for which the European Commission has not taken any adequacy decision, i.e., countries other than those listed here. In the United States, SMEs that do not participate in the Privacy Shield use the SCCs instead.

The Schrems Cases

On July 16, 2020, the Court delivered its long-awaited preliminary ruling on the “Schrems II case.” If you’re not familiar with the Schrems cases (there are two of them), here is a short summary.

The Schrems I Case

Maximillian Schrems is an Austrian national residing in Austria. He has been a Facebook user since 2008. In 2013, he lodged a complaint with the Irish Data Protection Commission (the “Commissioner”) whereby he requested that Facebook Ireland be prohibited from transferring his personal data to Facebook Inc. in the United States on the ground that the U.S. legal system did not ensure adequate protection of personal data held in the United States against U.S. public authorities’ surveillance activities. He referred to the revelations made by Edward Snowden concerning the activities of the U.S. intelligence services, in particular those of the National Security Agency. At that time, Facebook was relying on a legal instrument called the “Safe Harbor Framework” (later replaced by the Privacy Shield) to legitimize the transfer of personal data from the EU to the United States. The Commissioner rejected Mr. Schrems’ request and said the United States ensured an adequate level of protection through the Safe Harbor Framework.

Mr. Schrems then brought an action before the Irish High Court challenging the Commissioner’s decision and the Irish High Court referred the questions for a preliminary ruling to the Court. In 2015, the Court declared the Safe Harbor Framework invalid. The Commissioner’s rejection decision was annulled.

The Schrems II Case

Later, the Commissioner asked Mr. Schrems to reformulate his request based on the Court’s 2015 decision. Mr. Schrems maintained that the United States did not offer sufficient protection of personal data transferred to the United States. He requested that his personal data no longer be transferred from the EU to the United States. At this time, Facebook Ireland relied on the standard contractual clauses (last set adopted by the European Commission in Decision 2010/87) to legally transfer personal data from the EU to the United States.

In the meantime, the European Commission took a new decision in 2016 (Decision (EU) 2016/1250) on the adequacy of protection provided by the new EU-U.S. Privacy Shield and this new framework officially replaced the invalidated Safe Harbor Framework.

Since the Commissioner found that the outcome of Mr. Schrems’ request depended on the validity of the standard contractual clauses (Decision 2010/87), the Commissioner brought proceedings before the Irish High Court so it could refer (11) questions to the Court for a preliminary ruling.

In its preliminary ruling taken on July 16, 2020, the Court ruled that:

- GDPR also applies to processing of personal data by authorities of a third country for the purposes of public security, defense and state security (interpretation of article 2(1)(d)).

- The SCCs remain a valid instrument to transfer EU personal data to third countries (in the light of the Charter of Fundamental Rights), but the Court also ruled that:

- Since standard contractual clauses are not binding on the public authorities of the data recipient’s country, the individual has no remedy in the case of a lack of an adequate level of protection in that country. Therefore, the controller or processor, or the competent data protection authority, must evaluate whether the recipient’s country laws provide the appropriate safeguards, enforceable rights and effective legal remedies to ensure the same level of protection than in the EU. If this is not the case, either the controller must adopt supplementary measures to ensure compliance with the required level of protection (refer to paragraphs 133 and 134 of the preliminary ruling), or the transfer of personal data must stop (paragraph 135 of the preliminary ruling) and the SCCs must not be used. In other terms, SCCs must only be signed if the data recipient’s law allows the contractual parties to implement the clauses.

- The competent European Data Protection Authorities must suspend or prohibit a transfer of data to a third country covered by the SCCs if they deem that it is not possible to comply with those clauses in the third country.

- The Privacy Shield is invalid. This decision was motivated by the fact that:

- The “adherence to [the Privacy Shield principles] is limited to the extent necessary to meet national security, public interest, or law enforcement requirements (Privacy Shield, I.5). U.S. intelligence services are conducting massive surveillance activities (under section 702 of the FISA Amendments Act which authorizes U.S. authorities to collect communications of foreigners overseas for foreign intelligence purposes through the PRISM and UPSTREAM surveillance programs without any warrant since foreigners have no Fourth Amendment rights and under Executive Order 12333 and PPD-28 – refer to paragraphs 60 to 64, and 163 to 167 of the preliminary ruling for more details).

- The EU principle of proportionality, i.e., only processing personal data proportionate to the aim pursued, cannot be complied by Section 702 of the FISA, the Executive Order 12333 and PPD-28.

- EU citizens do not have the right to an effective remedy against U.S. authorities since the Fourth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, which constitutes, under U.S. law, the most important cause of action available to challenge unlawful surveillance, does not apply to EU citizens (see preliminary ruling, paragraphs 65, 181, and 182).

- In addition, the Court found that the ombudsman mechanism foreseen by the Privacy Shield does not address the limitations on the right to judicial protection. Indeed, the ombudsman reports directly to the Secretary of State (lack of independence from the executive) and does not have the power to adopt decisions binding on the U.S. intelligence services. Therefore, the ombudsperson mechanism to which the Privacy Shield Decision refers does not provide any cause of action before a body which offers the persons whose data is transferred to the United States guarantees essentially equivalent to those required by Article 47 of the Charter (paragraph 197 of the preliminary ruling).

How does this judgement affect U.S.-based businesses and freelance translators? What steps can we take?

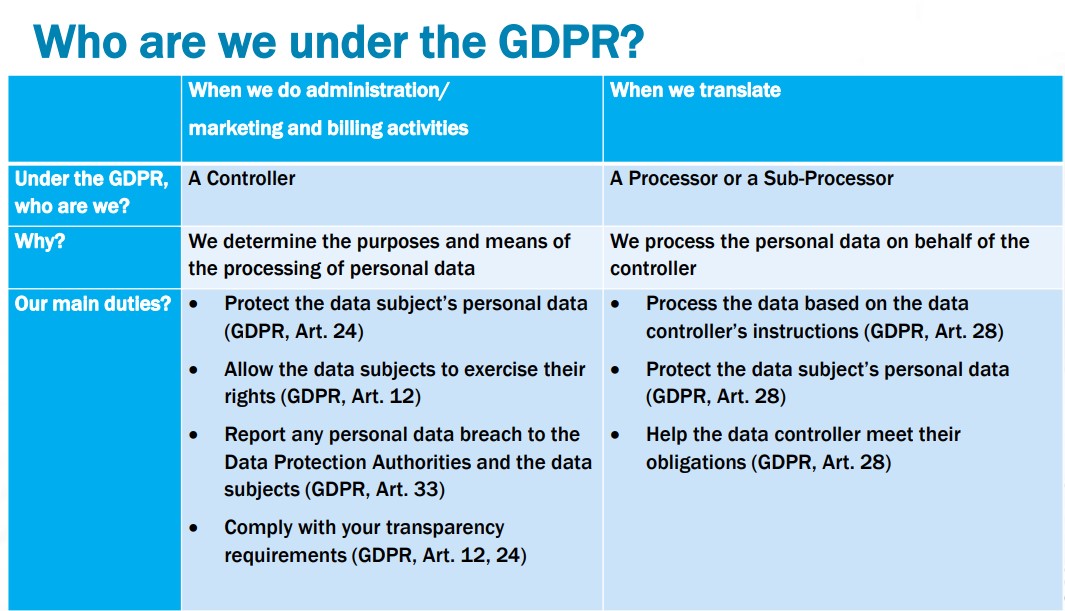

In the session on GDPR I gave at the 59th ATA conference, I drew up a table summarizing our GDPR roles as a translator:

How does the judgement affect our roles mentioned above?

To start with, the invalidation of the privacy shield started to apply right after the judgement. As a result, if you self-certified to the privacy shield to legally export personal data from the EU to the United States, you can no longer rely on this mechanism.

Your activities as a controller

- If you own a website and subscribed to the privacy shield, your privacy policy contains related specific language, and should be carefully updated. Please revert to your attorney, and keep in mind the Federal Trade Commission’s statement here.

- Carefully assess all the tools your website is using:

- Do you retain a copy of your emails on your website servers? Is it necessary? If a copy is kept, is it encrypted?

- Does your website use analytical and other non-necessary cookies and social media buttons? If these providers collect personal data (e.g. cookies that are not anonymized properly through your website), are those sent to the United States? Consider alternate services. E.g. Google Analytics could be substituted by e.g. matomo.org. Refer to ongoing legal actions in Europe here.

- Does your website collect personal data from your users (through a contact form, blog…)? Check with your attorney whether a real-time notice advising users their data will be transferred to and held in the United States, should be displayed on your website.

- Review your marketing activities (newsletters, solicitations…) and your billing and administration activities: To avoid any legal vacuum, the Court suggested entities should check whether some occasional international transfers can be covered by the GDPR derogations set forth in Article 49. I invite you to read the guidelines issued by the European Data Protection Board to learn further about this mechanism and check with your attorney to see if they can apply in this case.

Your activities as a processor

Most U.S. translators doing business with EU clients have actually signed SCCs to allow for the transfer of EU personal data that could be included in the files to translate. The amount of personal data you process really depends on the type of files you translate. (E.g. are you translating technical user manuals, or civil record documents all day?)

The entire community of privacy professionals (private entities and public authorities) has been waiting for further guidance by the European authorities to know how to use the SCCs (or other legal instruments more suitable to large undertakings) to transfer personal data from the EU to the United States. The FAQ issued by the European Data Protection Board reiterates the Court’s judgement:

- SCCs can still be used when both contracting parties can implement them. This is pretty straightforward, but many entities tended to sign SCCs without any extended review.

- Both contracting parties (the translator and their EEA client) must carry out an assessment of the circumstances of the transfer, and may have to take “supplementary measures” to ensure that the “U.S. law does not impinge on the adequate level of protection offered in the EEA.”

- If EEA clients find that appropriate safeguards cannot be ensured, they are required to suspend or end the transfer of personal data. If they intend to keep transferring data despite this conclusion, they must notify their competent data protection authority.

On September 4th, the European Data Protection Board announced it created a taskforce to assist both controllers and processors to identify and implement “supplementary measures” to ensure adequate protection when transferring personal data to third countries. While we wait for the outcome of this taskforce, we can certainly expect our EU clients to have a bigger focus on data privacy and security, and most probably sign amended (annexes to) SCCs. The German Baden-Württemberg Data Protection Authority has issued a first checklist in this regard here. NYOB also issued a sample questionnaire that you can refer to.

In the meantime, I personally think it is best to refrain from sticking our heads in the sand, and to adopt the highest privacy and security practices:

- List all tools you’re using/intending to use to store/exchange/back up files containing EU personal data and review their general terms and conditions. If you’re using cloud-based tools, are your provider’s servers located in the EEA or the United States?

- Assess each import of EU personal data, case per case, and identify whether your transfer is lawful, and whether you could do things differently.

- Use encryption techniques by all means to send/receive/store/back up your client’s confidential or sensitive information. Talk to your clients who do not use secure exchange platforms and find a solution to exchange files in a secure way. With the ongoing coronavirus crisis, our activities are more online than ever before, and cybercriminals are very active. Taking cybersecurity seriously is just the right thing to do, for many reasons. Feel free to refer to my slides here and here – although some sections are already outdated (data protection requirements evolve very fast – e.g. see the EDPS’s paper on the use of Microsoft products and services) or attend my cybersecurity session at the upcoming ATA annual conference.

- Talk to your clients: if the files you need to translate contain personal data, could these files be anonymized before they are sent to you?

As the world seems to have turned turtle, I want to emphasize Recital (4) of GDPR, “The right to the protection of personal data is not an absolute right.” My hope is the U.S. and EU authorities find an adapted solution for microbusinesses like us that transfer a small quantity of personal data. Moreover, elections are approaching in the United States. Could we expect an upcoming new executive decree on intelligence-gathering that could be the long-term solution, and maybe lead to a… third privacy shield? The future will tell. In the meantime, let’s continue to deliver utmost quality translation to our clients, and think of the best way to protect our clients’ materials.

About the Author:

Monique Longton, Leadership Council Member

Monique Longton has been translating legal and financial documents from English (primary source language), and Swedish and Danish (secondary source languages) to French for over 13 years. She is the business owner of Longton Linguistic Services (www.longtontranslation.com). Before, she worked for the banking and banking IT industry for 9 years. She holds a Master’s in Translation from the Faculty of Translation and Interpretation – EII School of International Interpreters at the University of Mons, Belgium, and a post-graduate degree in economics from the Catholic University of Leuven, New Leuven, Belgium. In 2004, she moved from Belgium to the USA. Her more recent expertise in the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and related data privacy and security matters was honed by translating numerous legal analyses, data protection impact assessments, security policies, privacy notices, and data processing agreements. As a Certified Information Privacy Professional for Europe, she stays on top of industry trends, attends data privacy and security events, and networks with privacy professionals. She is especially versed in the special GDPR challenges faced by US-based freelance linguists working for privacy-minded European clients.

Monique Longton has been translating legal and financial documents from English (primary source language), and Swedish and Danish (secondary source languages) to French for over 13 years. She is the business owner of Longton Linguistic Services (www.longtontranslation.com). Before, she worked for the banking and banking IT industry for 9 years. She holds a Master’s in Translation from the Faculty of Translation and Interpretation – EII School of International Interpreters at the University of Mons, Belgium, and a post-graduate degree in economics from the Catholic University of Leuven, New Leuven, Belgium. In 2004, she moved from Belgium to the USA. Her more recent expertise in the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and related data privacy and security matters was honed by translating numerous legal analyses, data protection impact assessments, security policies, privacy notices, and data processing agreements. As a Certified Information Privacy Professional for Europe, she stays on top of industry trends, attends data privacy and security events, and networks with privacy professionals. She is especially versed in the special GDPR challenges faced by US-based freelance linguists working for privacy-minded European clients.

Get in touch: monique@longtontranslation.com

Thank you for this thoroughly researched information! One question: what is an SME?