Translators who usually specialize in other niches sense a great opportunity in subtitling and have a newfound interest in translating audiovisual content. In some cases, they learn that existing clients own a trove of streaming videos in multiple formats. In others, they forecast that global audiences’ insatiable appetite for content, consumed on a variety of devices, will eventually stoke demand for translation. These new entrants should not underestimate the learning curve they will face.

Translators who usually specialize in other niches sense a great opportunity in subtitling and have a newfound interest in translating audiovisual content. In some cases, they learn that existing clients own a trove of streaming videos in multiple formats. In others, they forecast that global audiences’ insatiable appetite for content, consumed on a variety of devices, will eventually stoke demand for translation. These new entrants should not underestimate the learning curve they will face.

The subtitler is ideally a professional with the full range of linguistic and cultural capabilities, like any other translator, but they are also tech-savvy and have a good sense of “rhythm”: the rhythm of the spoken word; the rhythm of video, punctuated by cuts or scene changes; and the reading rhythm of the viewing public. Even with the full complement of the above skills and qualities, the subtitler’s work is often a target of criticism, mainly due to its visibility. Everyone sees your work up on screen and blames the subtitler when there is a glitch or the audience finds themselves distracted from the viewing experience by what they read. Sometimes the criticism is valid: the subtitler lacks experience or key capabilities. For instance, they can be excellent at timing but light on linguistic competence or vice versa. On the other hand, quite frequently the disapproval is off the mark as it is the critic who lacks knowledge of all of the constraints and challenges the professional faces to convey a message that is a product of fixed or moving images, voices, noises, etc.

Moreover, the domain of audiovisual translation has so many branches: it includes subtitling, captioning, dubbing, voice-over, multilingual broadcast, video games, and more. Being a competent professional across the entire domain requires having many distinct skills.

Besides technical complexities, audiovisual products are full of implicit messages in their dialogues or images. According to Jorge Díaz Cintas in “Teaching Subtitling at University” (2001), since most audiovisual content is rife with colloquialisms, the ideal scenario is for students to study subtitling after spending a year abroad, immersed in the language and culture of the foreign country. You may agree with that or not, but, in my opinion, hands-on understanding of cultural nuances definitely prepares you to better localize the message for your homeland’s audience. We can’t underestimate the necessity of localizing global videos, and the digital era has opened up a world of streaming platforms from which to choose.

Due to the complexity of the topic, I attend as many classes as I can to complement my growing experience. During ATA58, I searched for sessions related to audiovisual translation; however, as far as I could see, just two sessions out of 174 were focused on subtitling, which is about 1%. It would be great to see more educational opportunities at ATA and other professional venues to help translators with an interest in audiovisual work meet the steep learning curve.

At ATA58, I attended both of the AV sessions offered: an excellent one with Ana Gabriela Gonzalez Meade about “QUALITY REVIEWING PRACTICES FOR STREAMING MEDIA”, and a very entertaining one with Juan Baquero about “SUBTITLING CULTURAL REFERENCES.” They are humbly summarized here.

Session 1 – “GETTING DOWN TO BUSINESS – QUALITY REVIEWING PRACTICES FOR STREAMING MEDIA”, Ana Gabriela Gonzalez Meade

“Getting Down to Business” with Gaby helped me see, from the vantage point of her vast experience, how much the AVT industry has changed since the ‘90s. At inception there were only general guidelines, style guides applicable to all languages and a single glossary of terms. It grew to DETAILED LANGUAGE-SPECIFIC STYLE GUIDES for each client, audio and technical guides and training, performance reports, etc.

Currently with online streaming media, consumers are increasingly choosy and knowledgeable, demanding good quality in the final products. Consequently, AV translations have to be prepared by expert linguists that are leaders in their field, and proper revision is required to guarantee quality.

Besides describing error categories for subtitling and dubbing quality control, Gaby mentioned what QCers focus on when reviewing subtitles and dubbing scripts.

When reviewing translated dubbing scripts, the objective is having a lip-sync-based translation, molded by the nature of the character. The translation should convey accurately tone and meaning of the original, and the translator’s style and direction are usually respected. It is not common to suggest “better translations,” and punctuation and spelling should accommodate the voice actors in the booth. QC also needs to identify potentially tricky pronunciations.

When reviewing subtitles, even when a character speaks in a dialect, or with a speech impediment, accurate, neutral language has to be observed. Translations should follow the original as closely as possible, and text should adhere to each language’s governing grammatical rules. The text also adhered to each client company’s formatting guidelines. At all times readability is the priority, and uniformity needs to be enforced across the whole project.

Session 2 – “SUBTITLING CULTURAL REFERENCES”, Juan Baquero

My next session was with Juan Baquero. He showed some strategies for translating cultural references, using Pulp Fiction and Wild Tales as examples.

I loved Wild Tales, and Juan’s presentation explored Argentinian cultural references existing in that movie. I felt nostalgic for the time that I lived in Buenos Aires and was excited to see clips from the film sprinkled throughout to illustrate the points he was making.

As Juan says, while watching a movie, everyone said or heard someone saying: “They didn’t say that!” So he discussed some of the challenges faced by AV translation, listing some norms and constraints, such as:

1. A subtitle should start when the character starts talking and should end when the character stops talking.

2. Subtitles must be on screen for a minimum of one second, and a maximum of five.

3. We always need to have four frames (or 1/6th of a second) between subtitles

4. 38 characters per line (usually 2 lines, 76 characters).

5. Our words should match the images and not be in conflict with what the audience sees. (Inserts: capital letters)

6. Background noises (Background conversations, radio, etc.: italics)

The full list of constraints is even longer when you delve into elements of style, but a greater challenge is that the translator needs to identify and manage cultural references.

In the presentation, using scenes from Wild Tales, Juan guided us in identifying the strategy used in the translation of dialogues full of culturally-bound references, evaluating if there was some kind of cultural loss, and assessing the overall functional effectiveness of the strategy.

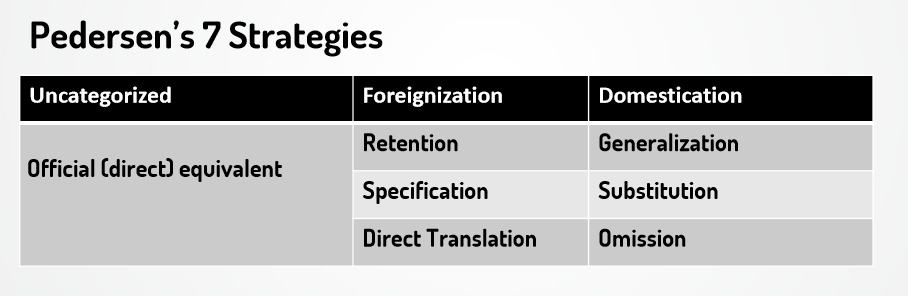

Using Venuti’s theory and Pedersen’s 7 strategies, we noticed that in 80% of the cases, the translation followed the domestication strategy, in which half of them used “substitution” as the main approach.

The study also demonstrated partial loss of the cultural references in 52% of the subtitles, and total loss in 36% of them. This may be due to a combination of these factors: subtitling “limitations”, client’s requests, the expected audience, and the translation strategy chosen.

As a result, according to Juan it is common to see a prioritization of functional equivalents over cultural references in a message. It is therefore expected to observe some loss of cultural references.

Fernanda Brandao-Galea has been working as a professional translator since 2011 after stints in diverse careers: first as a chemical engineer, then a law student, and also a project manager in Latin America IT sales. She specializes in areas that make use of her background, such as website localization and linguist for voice-based technologies, but also has a passion for audiovisual translation, especially subtitling. She is constantly deepening her professional and linguistic knowledge via courses and conferences. She has lived in Brazil and Argentina, but now resides in San Francisco, California, a hub for technology and entertainment. She can be found here.

Fernanda Brandao-Galea has been working as a professional translator since 2011 after stints in diverse careers: first as a chemical engineer, then a law student, and also a project manager in Latin America IT sales. She specializes in areas that make use of her background, such as website localization and linguist for voice-based technologies, but also has a passion for audiovisual translation, especially subtitling. She is constantly deepening her professional and linguistic knowledge via courses and conferences. She has lived in Brazil and Argentina, but now resides in San Francisco, California, a hub for technology and entertainment. She can be found here.

*A previous version of this post was originally published on Fernanda’s blog. Republished here with permission.

Leave a Reply