International trade and logistics translation bears a striking resemblance to scientific translation. Sound crazy? Bear with me a second.

Colleagues instinctively know not everyone has the subject matter expertise to translate chemistry-related texts. Although the same cannot necessarily be said for logistics company websites and shipping documents, that doesn’t make it any less true.

After giving a presentation on translation opportunities in the area of import/export in Colorado at the Colorado Translators Association’s Annual Conference in April 2018, a fellow FLD member approached me afterward to tell me she enjoyed my presentation and wanted to chat about how eerily similar her field of chemistry was to my field of international logistics and supply chain. We did a comparison:

| Chemistry Translation | International Logistics Translation | |

|---|---|---|

| Highly specialized terminology | ✔ | ✔ |

| Has its own degree programs (undergrad through post-grad levels) | ✔ | ✔ |

| Prior experience in field preferred for translators | ✔ | ✔ |

| Highly government-regulated industry | ✔ | ✔ |

| Subject matter continuing education required | ✔ | ✔ |

I believe international trade is a fascinating and complex area of specialization for a translator. And it is an area that offers substantial opportunities for those willing to put in the work to convince them of our value.

Finding My Niche

Ask some translators how they “picked” a specialization, and nine times out of ten, I bet they’d tell you their specialization picked them. That’s what happened to me. My experience in international trade didn’t come from a university. It came from working for one of the top 100 largest ocean importers into the United States. I was recruited to work there after college. I spent a couple years in sales, traveled to Chile to tour mills and see the manufacturing process, then I moved to the operations department where I managed imports into various regions in the US, oversaw third-party logistics provider (3PL) service levels, and handled any US customs issues that happened to pop up. Then one day, US customs came knocking on the door and announced their intention to conduct a focused assessment (the most intensive form of US customs audit) on the company. That was the “lucky” moment I was promoted to trade compliance manager and handed a nice big audit as a congratulatory gift. I spent the next two years working very closely with US customs auditors digging deep into several years of the company’s general ledgers, profit and loss statements and balance sheets to prove the legality of the company’s related-party transactions and their eligibility for the Chile Free Trade Agreement (CLFTA) and Generalized System of Preferences (another FTA).

As you can see from my varied experience, there’s a lot to this thing called international trade.

What Is International Trade?

Translators tend to think about the before and after of international trade – we think about translating the marketing materials, the websites where orders can be placed, the financial reporting after products are sold, but we often forget about what it takes to physically move cargo from one country to another, and there are mountains of paperwork and opportunities for translators during this phase of a product’s lifecycle.

Buying, selling and shipping and receiving goods across borders is not something you can just snap your fingers and do. It requires many partners (3PLs, a customs broker, maybe a freight forwarder, or a steam ship line contract if you’re not using a freight forwarder). Before you even start the physical process of importing goods, the seller and buyer have to define who will be responsible for each stage of the export and import process. An easy way to do that is agreeing on an Incoterm. Incoterms are rules created by the International Chamber of Commerce to facilitate the sale of goods. The terms were originally created in 1923, first published in 1936 and have been updated a handful of times since. You can buy a book explaining the incoterms from the ICC business bookstore. The latest update was released and published in 2010 and contains 11 different options that divide up which party is responsible for paying for each part of the export/import process. Below is an example of two different incoterms for illustration purposes:

CIF = Cost, Insurance and Freight

DDP = Delivery Duties Paid

| Incoterm | CIF | DDP |

|---|---|---|

| Loading on truck | Seller | Seller |

| Export Customs | Seller | Seller |

| Transport to port of export | Seller | Seller |

| Unloading at port of export | Seller | Seller |

| Vessel loading at port of export | Seller | Seller |

| SSL fees (carriage fees) | Seller | Seller |

| Insurance | Seller | Seller |

| Vessel unloading | Buyer | Seller |

| Loading on truck at port of import | Buyer | Seller |

| Transport to dest. | Buyer | Seller |

| Import customs | Buyer | Seller |

| Import duties | Buyer | Seller |

These terms have to be decided on no matter what type of relationship you have with the exporter. You could be buying and importing product from a random company, or you could be importing product from a subsidiary – either way, agreements and terms need to be negotiated on and drawn up, which creates contracts in another language that need to be translated.

How It Works

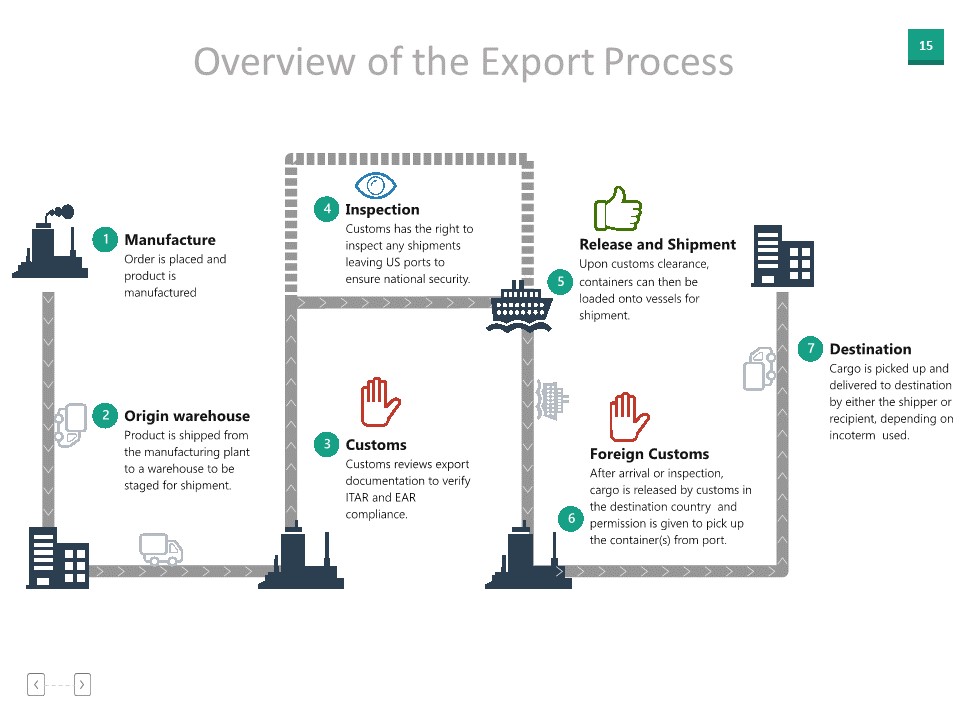

Below is a flowchart illustrating a simple import:

Remember — once cargo arrives to the United States, that’s not the end of its journey, but rather the beginning of a whole new supply chain journey over here that will most likely include distribution centers (DCs), smaller warehouses and either truck or rail shipments across the US.

Exporting is very similar to importing, but backwards. One difference is that US customs can hold and inspect your shipments before they leave the US, and then they also have to go through customs at the foreign destination. Customs wants to inspect outgoing cargo to make sure that no threats to national security are leaving the country.

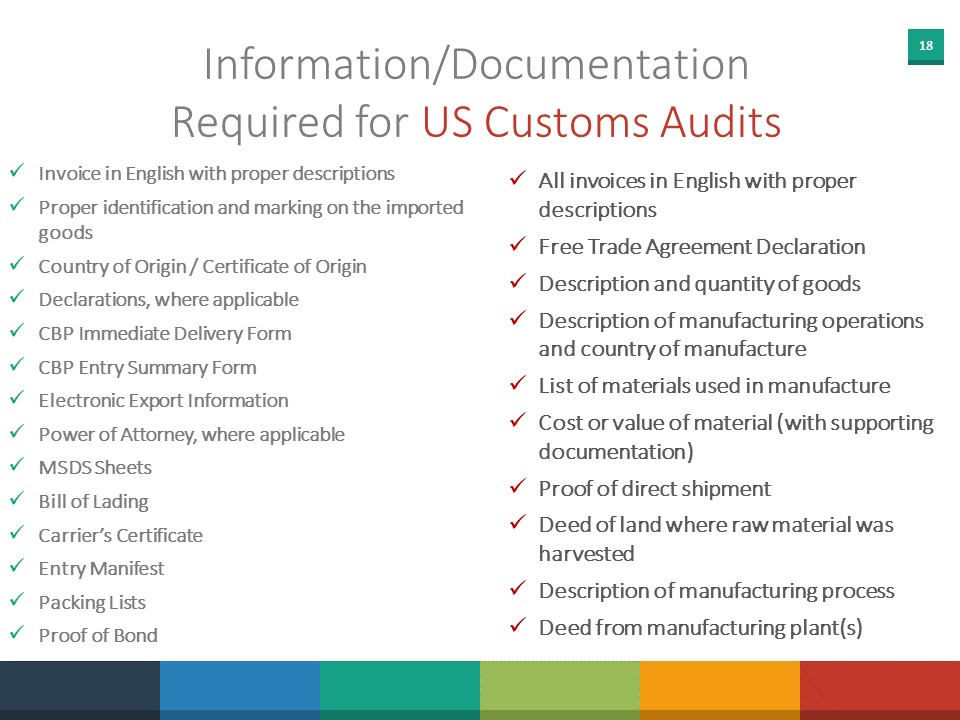

Now that we’ve seen how to physically move cargo from one country to another, let’s take a look at the documentation US Customs and Border Protection requires each shipment to have in order to clear customs and enter the United States. Keep in mind that all of this documentation needs to be either translated or originally written in English. All of these documents come from the exporter:

And if an importer is lucky enough to be selected for a focused assessment, that list of documents required by CBP increases exponentially:

Other Opportunities in the Supply Chain

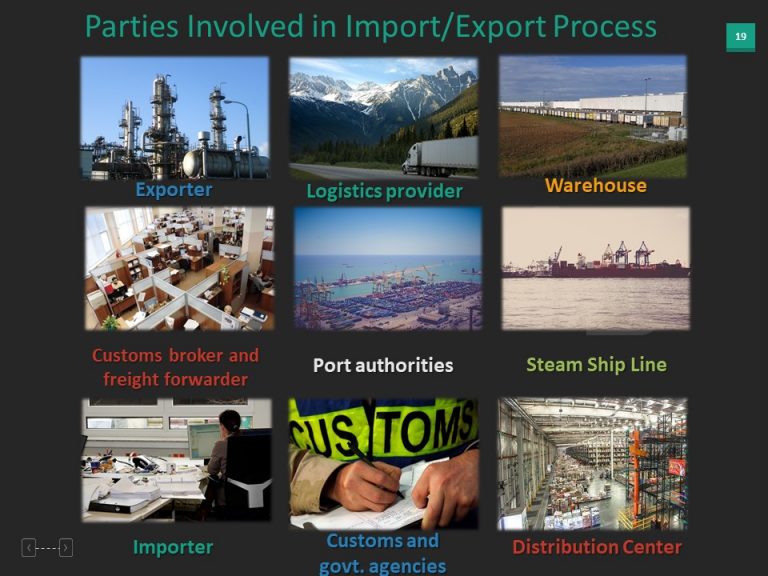

Most translation opportunities would come from the importer or exporter, but they are not the only parties involved in the process. There may be opportunities with some of the other parties involved in importing – especially with customs brokers and freight forwarders, because some importers and exporters are less knowledgeable than others and outsource the entire process to a freight forwarder or customs broker. Here is a list of all the different organizations that either create, process or review multilingual documents:

That being said, out of all the parties mentioned above, US Customs and Border Protection and other government entities that work alongside customs are the parties that will insist on quality translations when needed.

What Is US Customs and Border Protection?

US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) is the largest federal law enforcement agency in the US. Its primary objective is to prevent terrorists and weapons of mass destruction from entering the United States and it is also responsible for border patrol, regulating imports and exports, collecting duties, transportation checks, trade enforcement and trade facilitation.

When could CBP ask for translations?

- During Quick Response Audits (very specific audits focusing on one single item)

- During Focused Assessments

- If an importer is working with CBP to join the Importer Self-Assessment Program (ISA)

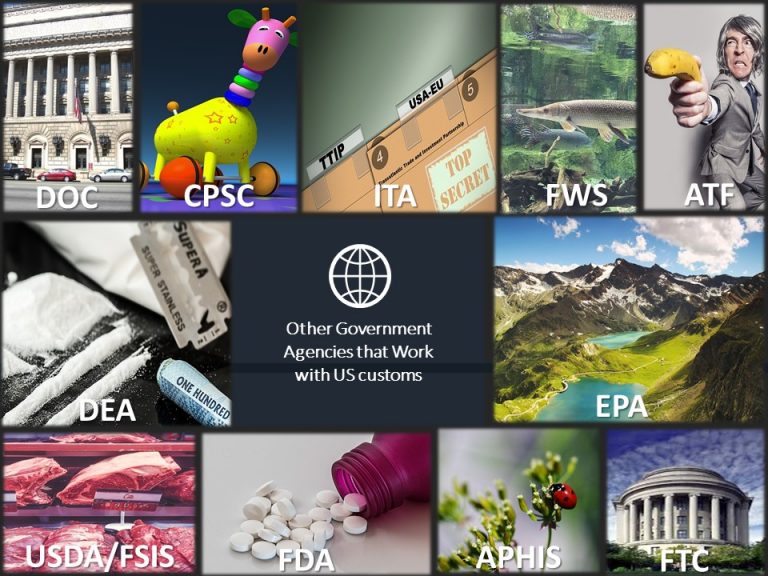

In addition to Customs, the US government has other agencies that are responsible for enforcing trade laws and consumer protection laws, so these agencies work with customs during the import and clearance process as well:

Want to Learn More?

If you really want to go deep, several universities offer international logistics/supply chain programs. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Michigan State, Penn State and the University of Tennessee all have distinguished programs. There are also a lot of MOOCs related to international trade, import/export, etc. Check out Coursera and Springboard. Large customs brokers and international trade law firms offer online and in-person courses. Sandler and Travis (STTAS) offers webinars all the time. CBP, some customs brokers and some international trade law firms offer free newsletters you can sign up for. Check out the census bureau and cbp.gov. CBP, Census Bureau, the Bureau of Industry and Security and other government entities offer abundant resources. Lastly, you can get certified – IIEI, the World Academy and other organizations offer various international trade certification courses (links are below).

Training Resources

- Online courses and MOOCs

- Certifications offered

- US government resources

- Free international trade newsletters

Amanda N. Williams is an ATA-certified French to English translator specialized in business, international trade and financial translation. You can find her on Twitter as the Adorkable Translator (@Adorkable_Trans), on her website at www.mirrorimagetranslations.com or reach her via email at amanda@mirrorimagetranslations.com.