by Gabriela Lemoine

How do you translate a script that is going to be used for dubbing? What is adaptation for synchronization? In this overview of my presentation at ATA61, I will summarize answers to these questions, drawing on examples from many real movies and TV shows dubbed in Spanish. These clips were generously provided by Sebastián Arias, who has 15 years of experience as a dubbing director. If you attended the conference, you can always watch the recording!

There has been an increasing demand for translation for voice-over and dubbing over recent years, as more and more audiovisual content is being produced. In general, voice-over is used for documentaries or narration, while dubbing, which requires lip synchronization, is used for films and series, especially those for children.

Dubbing Translation: Two Potential Pitfalls

Usually, the most noticeable problem when we’re watching a movie is lack of timing synchronization, which happens when the voices are not heard at the same time as the faces speaking on the screen. Another very visible issue is when the shape of the mouth does not match the sounds in that particular line. This is a lack of lip synchronization. For example, if the actor says “dog” in the film using a big, long “o” sound, the straightforward translation perro does not match the lips very well, and perhaps a word like can would fit better.

Although timing problems could just be a post-production issue, other factors affecting speech translated for dubbing need to be taken into account to avoid unintended results.

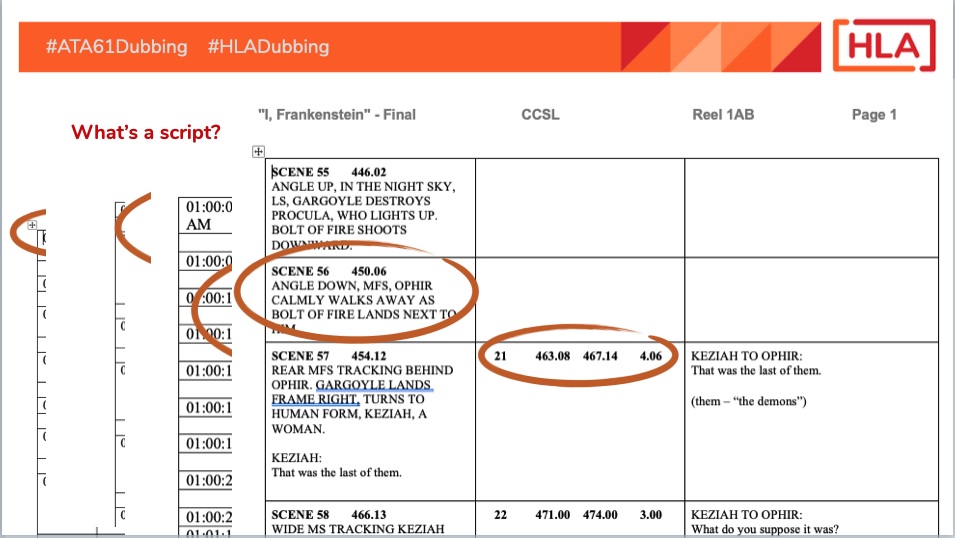

It all starts with the original language script. Scripts can vary, but all have a few common elements:

- A heading with information about the film or series

- Timecodes, showing the times when an utterance starts and ends

- Characters or, if applicable, a narrator

- The actual dialogue

There could also be additional information such as noises or other utterances, transitions from one scene to the next, the number of scenes, and more scene description that affects the tone –all

helpful information for the dubbing director.

Understanding scripts is important because they give you cues that will help you create a translation the director will not have to change much when the dubbing process starts.

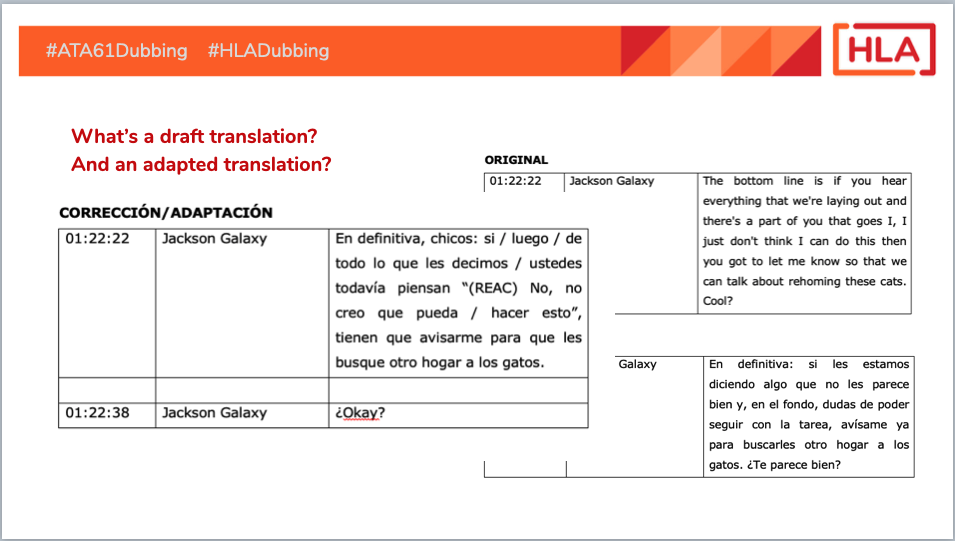

When translating, a script may need to be adapted, which is sometimes called adjustment, so the two most visible elements of speech are preserved: timing and lip sync.

Timing

There are three main elements to dialogue timing:

- The duration of an utterance, including the time it starts and ends. This is normally measured in seconds and frames.

- How many syllables an utterance has and where the actor places emphasis. This emphasis is called an “impulse”.

- Any pauses, including hesitation.

For example, “Just go unnoticed.” could be translated as “Simplemente pasar desapercibida.”

Although this translation is very accurate, it is too long for the original utterance, which was said very fast, in about three impulses (just-gounNOticed). An adjusted translation could be “Y que nadie me note,” which can also be said in two or three impulses (yqueNAdie-meNOte).

On the other hand, a translation could also be too short. The original sentence “I am nervous,” said with emphasis and slowly (I-AM-NER-vous), was originally translated as “Lo estoy,” which would have to be adjusted to “Sí, estoy nerviosa.”

Lip Sync

When considering lip sync, the most visible sounds are:

- A, O, and E vowel sounds: we’d need to pay attention to the shape of the mouth

- Labial consonants (M, B, V) sounds: place of articulation with the lips closed

- Fricative consonants (F and V) sounds: place of articulation with the upper teeth touching the bottom lip

These sounds are the most visible, but they aren’t the only sounds we should focus on. The truth is it depends on how the actor has spoken: fast, slowly, enunciating a lot or barely moving their lips, yelling, laughing, whispering, crying, or maybe the actor’s mouth or face are not even visible in a particular scene.

The camera shot is also a factor. The director may have done a very big close up of the face and the mouth, or shot the person sideways, at a distance, or while walking or running. The more visible the mouth is, the more adjusted the translation will have to be for a good viewer experience.

In addition to the specific examples reviewed here, other strategies were outlined in the presentation, including: shortening or adding speech when there is a change of scene or silence in the original film; reproducing chopped speech, hesitation and false starts which are typical of non-scripted shows; assimilating sounds to a closed or open mouth (“we shall see” vs. Ahora te diré); plays on words in both the source and target language; reproducing humor and punch lines; reproducing or substituting accents; adapting idioms; substituting or avoiding regionalisms; using or avoiding profanity according to specific country ratings; converting measurement units in keeping with what’s on the screen; reflecting the character’s personal traits; and shifting word order to improve lip sync.

Other useful Spanish translation solutions for common phrases:

- Nice: Así

- Oh my god: Ay, por Dios – No lo puedo creer

- You’re killing me: En serio me frustras

- Please: ¿Podría…?

- OK: ¿Oíste?

- Go! Go!: ¡Corran!

- Run! Run!: ¡Salgan!

- How?: ¿Qué hacen?

- Bitch: Fantoche

- China: Vajilla

To conclude, a perfectly accurate translation of a script may be useless for dubbing. At the same time, when adjusting a translation for dubbing, we can use strategies like adding or omitting text that are not acceptable for other uses. To maintain timing and lip synchronization, anything is possible, and there is probably more than one solution. Take your creativity “to infinity and beyond”!