by Agnieszka Szarkowska and Łukasz Dutka

How Can We Learn More About How You Watch Subtitles?

As researchers, we’re always trying to learn more. When it comes to subtitling or captioning (we’ll be talking about subtitles here, but it all applies to captions as well), what we can do is collect subtitles and analyze them. We can calculate how many words there are, how many characters are displayed per second or how cultural references are translated from one language to another.

And when we want to learn more about how people watch subtitled content and whether subtitles are fit for purpose, we can meet with a group of viewers and conduct interviews or send out an online questionnaire. While all of this can be useful, there are some challenges. Some people are not very keen on filling out questionnaires (“Another questionnaire?”). And when asked about subtitles, viewers can be biased in their opinions or misrepresent their experience (because they don’t remember it well). We could ask you questions immediately after you have seen a subtitle, but imagine that you’re watching an episode of your favorite TV series, and we’re pausing it every few seconds to ask you whether you understood or if you had enough time to read all of the words. You would probably be furious at us for ruining your viewing experience. And it wouldn’t be a good representation of how you normally watch content anyway.

Our aim is to collect information that is as objective as possible and gives us insight into how you watch subtitles as a viewer and how your brain processes the video, the audio and the text. In the ideal world, we would love to have a peek into your brain as you watch subtitled content. (But if you’re like us, you’re probably not that excited at the prospect of having your skull opened, are you?). So how can we get insight into what is happening in your brain as you binge-watch another series?

Luckily, we now have other, less invasive ways of looking into your brain with technologies such as EEG (putting electrodes to your skin to measure the electrical activity of your brain). And then there’s our favorite toy: eye tracking. We’ll focus on this one today.

A Window into the Brain

Eye tracking doesn’t actually let us look into your brain. It allows us to record your eye movements so that we know how your eyes move and which areas attract your attention. Perhaps you’re wondering: but wasn’t our objective to look into the brain? Have you heard the saying that eyes are a window to the soul? While we don’t know about the soul, as researchers, we certainly believe that the eyes are a window to the brain. In fancy research terms, we call it the eye-mind hypothesis. We assume that when your eyes are looking at something, your brain is processing it more or less at the same time. And if your eyes stay on a certain area longer, this means your brain is taking longer to process it – possibly because it’s more difficult (or more interesting!). This way, by analyzing the movements of your eyes, we can learn more about how your brain processes subtitles (and your skull can remain intact).

Fig. 1. An EyeLink desktop eyetracker with a PC set-up Photo: Agnieszka Szarkowska.

So, what we do is we use an eye tracker (see Fig. 1), which is essentially an advanced infrared camera that records your eye movements. We usually put it on a desk in front of you as you watch some content on a screen (there is also a head-mounted version but we prefer not to ruin your hair). Based on this recording, we know which areas attracted your attention and how your eyes moved from one area to another.

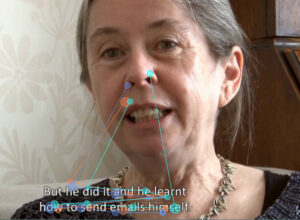

Fig. 2. A scanpath of viewers watching a subtitled video (“Joining the dots” directed by Pablo Romero Fresco) PHOTO: Agnieszka Szarkowska, authorized to use by Pablo Romero-Fresco.

The picture above illustrates how three viewers looked at this shot and how they read the accompanying subtitle. Each viewer is represented by a different colour. Each little dot that you can see on the images corresponds to a fixation, that is, a moment when a viewer fixates (stays relatively still) on an area. In other words, eyes move to this place and stay there for a while. Then the eyes move somewhere else. This movement, shown here by a continuous line, is called a saccade. There’s a fixation, a saccade and a new fixation. So now you know how people watch subtitled videos.

Eye-Tracking Can Help Us Verify Long-Standing Assumptions About Subtitling

Eye-tracking research into subtitling goes back to the early 1980s, when Gery d’Ydewalle, Professor of Psychology, and his research team in Belgium set off to study how viewers engage with subtitled videos. Their research set the stage for later studies and some of their findings remain valid today. So, what do eye-tracking studies tell us about the reading of subtitles?

Automatic Reading Behavior

Subtitles attract viewers’ attention, regardless of whether viewers depend on them for understanding or not. So as a viewer you are very likely to be reading subtitles even if you can understand the language of the soundtrack or if you don’t know the language of the subtitles! To people who are accustomed to subtitles, their reading is “automatic” and “effortless”, as stated by prof. D’Ydewalle, provided that the subtitles are good quality of course.

Fig. 3. Subtitles are great gaze attractors. By quickly appearing and disappearing on screen, they attract viewers’ attention. Compare the screenshot on top with a heatmap visualization below in the fist picture showing a news anchor in a TV news bulletin. Viewers’ attention, visualized as red blobs (the redder the area, the more attention it attracted), is mostly on her face. However, the moment a subtitle appears (the screenshot below), viewers shift their attention to read it, at the cost of looking at the presenter: Images: Royalty-free stock photos from Canva and graphic elements by Canva.

What Attracts Your Attention the Most?

Perhaps you noticed it’s human faces that attract a lot of attention. As human beings, we’re very much interested in other humans and especially their faces. It’s interesting that people who can hear well tend to look at the eyes, while if you have hearing loss, you will tend to look more at the mouth. That’s because looking at lip movements might help you understand speech better.

Thanks to research by Prof. d’Ydewalle and his team, we know that subtitles are a bit like faces and they attract a lot of attention, too. That’s not surprising because we need subtitles to understand the scene. But do you know that your eyes will try to read subtitles even when you don’t need to or if they are in a language that you don’t understand?

For instance, we don’t understand Chinese but a subtitle in Chinese appears, our eyes would move to this area, trying to read this subtitle.You have to consciously decide to start ignoring subtitles. That’s because when subtitles appear and disappear, all this creates something that looks like movement on screen. And any sort of movement is something that attracts our eyes a lot.

Not All Words Are Read in the Same Way

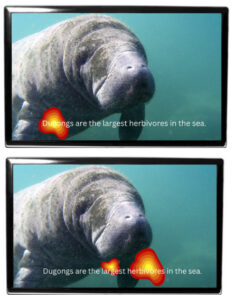

Despite what many people may think, when reading subtitles, viewers do not focus on all words in the same way (see Fig. 4). In fact, they don’t even read every single word in the subtitle: about 30% words are skipped during reading. Most of them are short, grammatical words such as articles, pronouns, prepositions or conjunctions.

What viewers tend to focus on more are long words, especially those that are not very common (linguists call them “low-frequency words”). What does it mean for you as a subtitler? If you have long, rare words in the video you are translating, make sure you give viewers enough time to read them, as it is very likely that people will focus on these words and will gaze at them longer than usual.

Fig. 4. Heatmaps showing viewers looking at different words in the subtitles. Note that in this subtitle the words such as “dugongs” and “herbivores” are much more likely to attract viewers’ attention than more common words, such as “in”, “the” or “sea”. Images: Royalty-free stock photos from Canva and graphic elements by Canva.

Watching or Reading?

The moment a subtitle appears, it attracts your attention. Usually, you read it in a number of fixations depending on how many words there are in the subtitle. Once you have finished reading, you go back to the center of the screen, exploring the images (see Fig. 2). And then another subtitle appears, and your eyes move again to this subtitle, and you read it, and go back to looking at the images. In other words, you switch from the images to the subtitle and then back to the images.

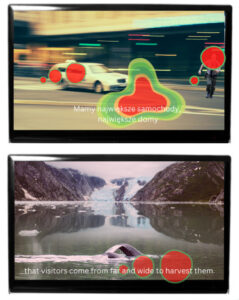

Now, if there are consecutive subtitles, one after another, without longer gaps in between, and all these subtitles have high reading speeds, once you have read one subtitle, you might have very little or no time left to look at the images because another subtitle appears. In such a case, a lot of your attention will be on subtitles, and you might miss what’s happening in the images (see Fig. 5).

When this happens, instead of watching the film, you’re actually just reading. And while reading is great, if you just wanted to read, you would probably sit down with a book in your lap, right? And then, in the worst-case scenario, if reading speeds are very high, you might not have enough time to fully read subtitles. Before you get to fixate on the last words in the current subtitle, it will disappear, substituted by a new subtitle. In such a case, you will start missing bits of dialogue, you might struggle to understand what’s going on, or you’ll be confused. Of course, you can pause the video to reread the subtitle, or you can rewind the video if you missed something, and you can watch the scene again (unless you’re in the cinema). But this is not a comfortable viewing experience, so at some point you will probably just quit watching.

Reading Speed

A great deal of eye-tracking research on subtitling was done to find the impact of subtitle speed on viewers. Searching for the ideal reading speed to be included in subtitling guidelines is like looking for the Holy Grail. Reading speed depends on so many factors that it’s not really possible to say what the best reading speed is (but if you really want to know, some recent research led by Prof. Jan-Louis Kruger in Australia has shown that 28 cps is way too fast). The factors that affect the way we read subtitles include the complexity of the scene (who much is going on visually?), how fast the characters are talking, what they are talking about (rocket science or just chit chat?), what words they are using (high or low frequency?), whether we understand the language of the soundtrack, and so much more.

Fig. 5. When subtitle speed is too high, viewers may spend a lot of time reading the subtitle and as a result they may not have enough time to follow the image. Images: Royalty-free stock photos from Canva and graphic elements by Canva.

How Much Time Do Viewers Spend on Reading Subtitles vs. Watching The Images?

Thanks to eye-tracking research we know that the higher the subtitle speed, the more time viewers spend gazing at subtitles. This typically ranges from about a third to about half of the time when the subtitle is on screen. Why does it matter? As subtitles are never viewed on their own, but are always shown together with a video, we subtitlers need to allow viewers sufficient time to read the text and follow the images.

Shot Changes

When you start learning subtitling, you are taught one of the most fundamental rules related to timing subtitles: they should not straddle shot changes. One of the reasons often given to explain this rule is when a subtitle crosses a shot change, viewers will go back with their gaze to re-read this subtitle. Having tested this assumption with eye tracking a few years ago, however, we weren’t able to confirm it. In the study, we showed viewers clips with subtitles which straddled shot changes for at least 20 frames on each side of the shot change. We found that the vast majority of viewers simply continued reading the subtitles or gazing at the on-screen action, and they in fact did not return with their eyes to re-read the subtitles. Yet, this is not to say that subtitles can now cross shot changes in every possible way. Personally, viewers find the flickering effect – when subtitles are displayed over a shot change for just a few frames – very irritating. But we have no hard research-based evidence to support it.

Subtitle Display Mode

Testing live subtitles displayed in the scrolling mode, Prof. Pablo Romero-Fresco noted that scrolling subtitles are much more difficult to read than subtitles displayed in blocks, as words appear and disappear erratically. He metaphorically compared the subtitle reading process to walking on quicksand.

The conclusion from his study was that subtitles should be displayed in blocks (as is the case with pre-recorded subtitling) rather than in the scrolling/roll-up mode. However, block display results in a larger delay, which is problematic in live subtitling, so it is unlikely that broadcasters will decide to change the scrolling display any time soon.

How Subtitlers Work

Last but not least, thanks to eye-tracking research, we have also been able to study differences between how professionals and trainee subtitlers work and use subtitling software. For instance, novices had more rounds of spotting-translating-revision and they relied much more on the mouse. They also tended to watch the entire video first, before proceeding to subtitling. Professionals, on the other hand, used keyboard shortcuts much more (probably with less wrist pain!) and they completed the task faster than novices.

What’s Next?

Having reached the end of this article, you can see that eye tracking has helped us better understand how we engage with subtitled content (without having to cut viewers’ skulls). But this is just the beginning! There are plenty of other questions that remain unanswered. If you have any ideas on what else should be studied with eye tracking when it comes to subtitling, don’t hesitate to drop us a line!

Agnieszka Szarkowska is a researcher, academic teacher, translator trainer, and audiovisual translation consultant. She works as University Professor at the University of Warsaw, where she is the Head of AVT Lab, a research group that works on audiovisual translation. She is one of the founders of AVT Masterclass, an online platform that provides training in subtitling and media localization. Contact: a.szarkowska@uw.edu.pl

Łukasz Dutka is an audiovisual translator, subtitling trainer and expert in multilingual media localization workflows and media accessibility. He’s one of the founders of AVT Masterclass, a director of the Global Alliance of Speech-to-Text Captioning, and a member of the Management Board of Dostepni.eu, an accessibility services provider. He’s experienced in interlingual subtitling, subtitle template creation, postproduction captioning, live captioning, theatre surtitling and live events accessibility. Contact: lukasz@lukaszdutka.pl