by Ana Salotti

This year at ATA has been particularly special for audiovisual professionals. For the first time in decades of a booming audiovisual industry, we finally have a specialized Division for those who work in the audiovisual field, a true milestone in the United States and abroad.

However, by the time the brand new AVD was established in late August this year, the wheels for ATA59 had already been turning; sessions and distinguished speakers had all been selected and confirmed. Audiovisual translation was not a distinctive conference session category. Yet five sessions were accepted for ATA59: The Savvy Subtitler by Jutta Diel-Dominique and Mylène Vialard; The Subtleties of Subtitling by Britta Noack and Nanette Gobel; Lack of Feedback Effect: A Most Effective Audiovisual Translation Training Aid and Herramientas básicas de la Real Academia y recursos afines en la TAV both presented by Ana Gabriela González Meade; and Traducción de subtítulos by Lina Morales and Kathy Byrd. Let’s have a look at each one.

The Savvy Subtitler

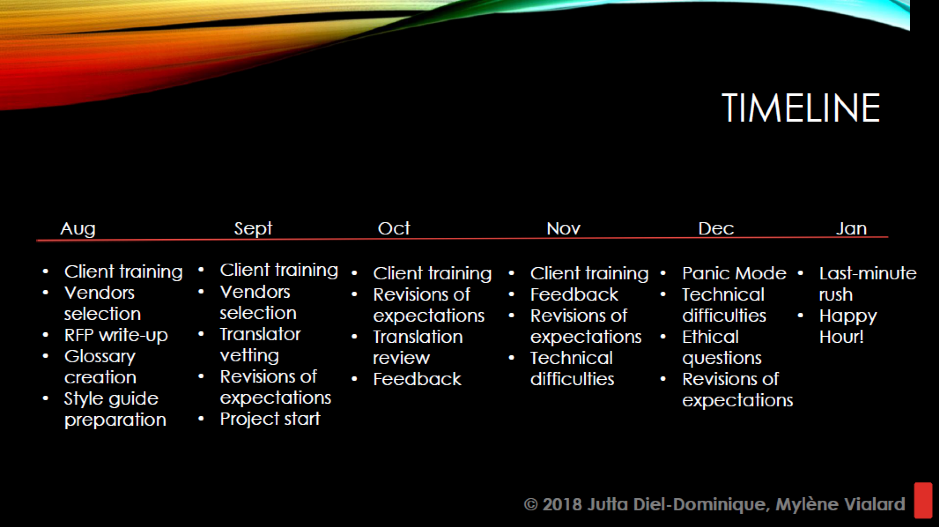

In their session, Jutta and Mylène started by engaging with the audience, asking who had experience in subtitling. Most people did not. The session’s main focus was to draw on their experience gained throughout a five-month subtitling coordination and quality assurance project mainly in German and French. They worked with more than 270 documentaries and movies, 140 dubbing scripts, localized one website and engaged five language service providers. They summarized it in an insightful timeline that included all their prep time (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Jutta and Mylène’s timeline showing their workflow managing a huge subtitling project.

Figure 1: Jutta and Mylène’s timeline showing their workflow managing a huge subtitling project.

Then they delved into the what’s, where’s and why’s of audiovisual translation as a big translation niche, basing their information on Cisco’s White Paper on internet traffic and online video creation 2016-2021. According to their data, it would take an individual more than 5 million years to watch the amount of video that will cross global IP networks each month in 2021!

They also made a point to the audience that your experience as a freelance translator matters, and it matters a lot. They showed some subtitling basics to get you started in the field, like where to get your resources, such as Netflix Timed Text Style Guides, BBC Guidelines and TED Translator Resources, the different file formats you can create subtitles in, and subtitling tools, like the free Aegisub and Subtitle Edit, the paid ones like MacCaptions ($1,750), WinCaps and Poliscript ($22.14 to $32.56 per month). They also warned the audience that the only CAT tools that allows working with subtitles are Smartling, Transifex and Wordbee—I also know MemoQ does as well— but pointed out that none are ideal.

They gave their fair share of tips for newcomers. They advised to first try any of the free subtitling tools available and only then move on to the paid options, exploring what works for you and your client. They also gave some tips on how to work smartly with agencies in audiovisual projects. They said agencies usually want to know, straight from our résumés, how much of our actual translation work is audiovisual-related, a list of productions, movies or shows that we have worked on and our rates, but warned, “Too low a rate per minute is a no go!” Agencies prefer translators who work with subtitling software, ideally paid ones, and tend to select translators based on a triple R rule: responsiveness, responsibility, read instructions/style guides. In contrast, working for direct clients in audiovisual projects may require translators to take the lead and advise clients on what they actually need. Direct clients tend to care more about the triple D rule: deadlines, deliverables and dollars.

Lastly, they gave an interesting perspective on rates. First, they quantified how much time translating subtitles would take you. According to their calculations, it takes 6 minutes to translate 1 minute of audio without transcribing it. If you need to transcribe it first, the same math applies. If you were to also edit timings and create synced subtitles, it would take you 1 hour of work to do 4 minutes of film. But this will depend on the media genre and the translator’s experience. An action movie doesn’t take the same amount of time than a documentary or an educational video, just to name a few different genres in audiovisual content.

The Subtleties of Subtitling

This session, presented by Britta Noack and Nanette Gobel, focused on how to translate jokes, proverbs and other cultural references into German functional equivalents, while still conforming to subtitling restrictions, like reading speed, character limits, timing specs and other client’s guidelines. Britta and Nanette drew on their extensive experience as subtitlers and audiovisual translators, and provided a plethora of food for thought.

They started off with their personal introductions. Britta suitably used the movie Who Needs Sleep? (2006) to introduce herself as a sleepless, tireless mom and translator, formerly specialized in gaming translation and now in the audiovisual field. Nanette told us her path from the literary and interpretation worlds to the audiovisual one, which she defined as a great way to join the best of both worlds into one.

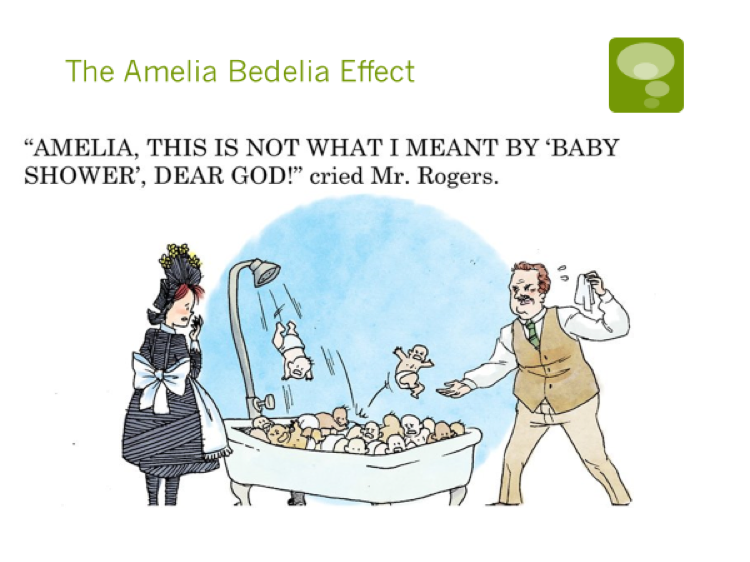

Then they started out by presenting a cartoon that read, “I’m watching the fashion show. It’s clothes captioned.” They engaged the audience, exploring different options into several languages, some matching the homonym, others reproducing the alliteration, generalizing or even neutralizing the phrase. This one certainly defied everyone’s creativity. They also made a point that sometimes you may find the perfect match for a pun or a joke after hours of racking your brains, only to find out that it’s too long for the subtitle space, thus rendering it useless. They kept their audience on the edge of their seats as they showed one funny example after the other from TV shows and documentaries, while wittingly presenting audiovisual restrictions, like crowded scenes with on-screen texts and subtitles, or puns in sync with a specific set of visuals that only work in the source language. A case in point is shown in Figure 2, so ubiquitous in audiovisual translation that has been known as “the Amelia Bedelia Effect”.

Figure 2: Example to show the usual complexity of audiovisual materials that tend to use puns working with available visuals and only in the literal sense of the source language, complicating translators’ lives.

Figure 2: Example to show the usual complexity of audiovisual materials that tend to use puns working with available visuals and only in the literal sense of the source language, complicating translators’ lives.

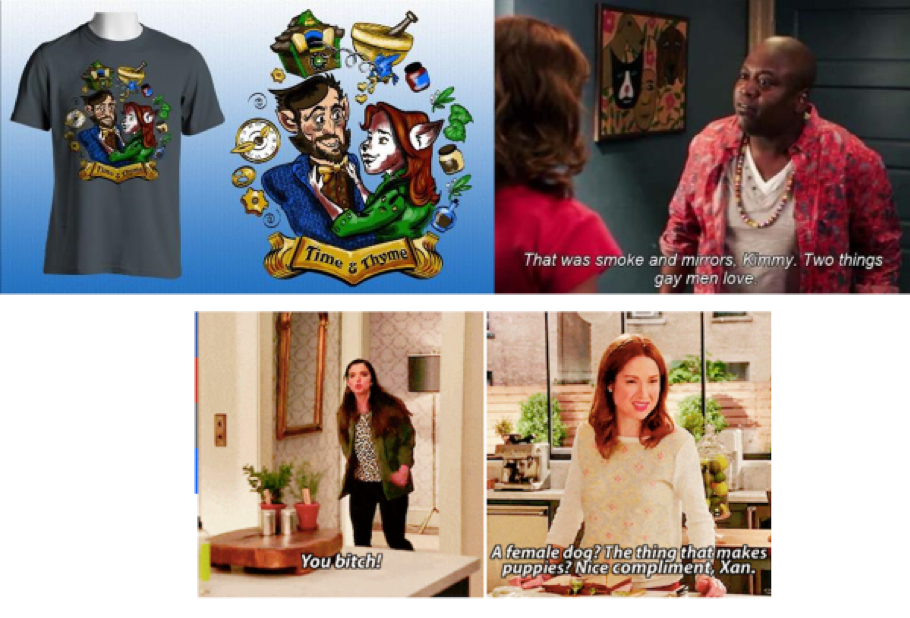

The presenters engaged with the audience trying to find equivalents in funny, yet complex examples (see Figure 3 for more). They also touched upon uncensored curse words and advised translators to consider the jarring effect that reading an offensive curse word on screen may have on specific audiences when compared to only hearing it. The power of the written word.

Figure 3: More audiovisual examples where translation needs to get creative.

Figure 3: More audiovisual examples where translation needs to get creative.

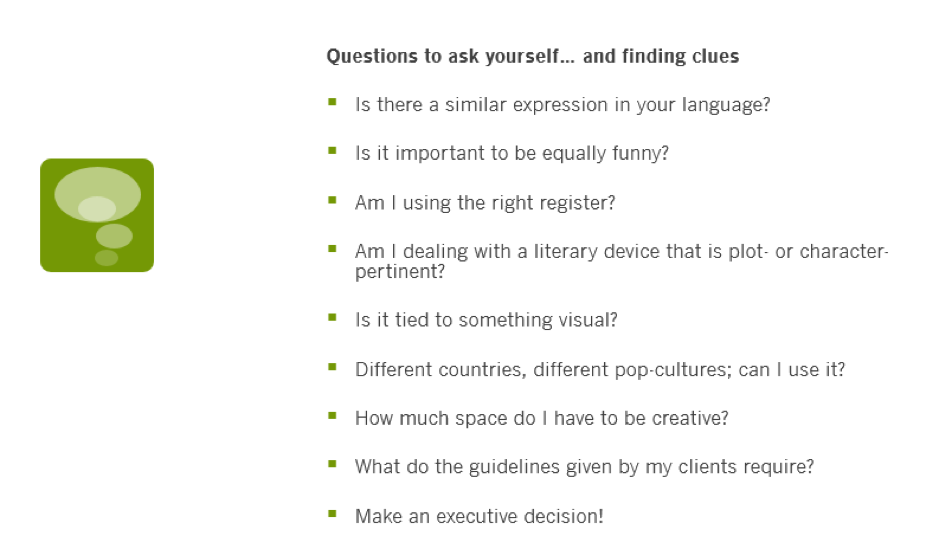

Finally, they shared a few tips on how to deal with humor, slang, curse words and other audiovisual pet hates, warning there are no hard-set rules and it all comes down to your experience and judgement (see Figure 4 for specific tips).

Figure 4: Tips on how to deal with puns, jokes, proverbs or curse words in audiovisual media.

Figure 4: Tips on how to deal with puns, jokes, proverbs or curse words in audiovisual media.

Herramientas básicas de la Real Academia y recursos afines en la TAV

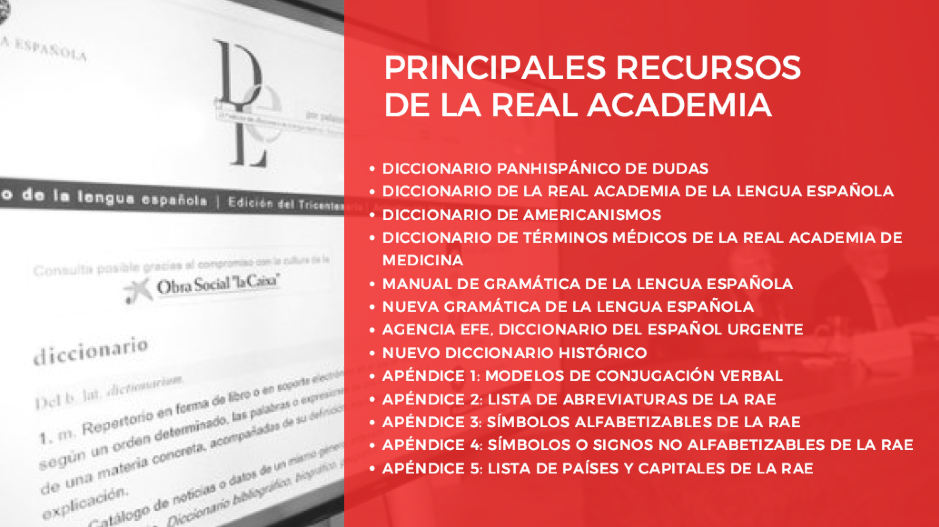

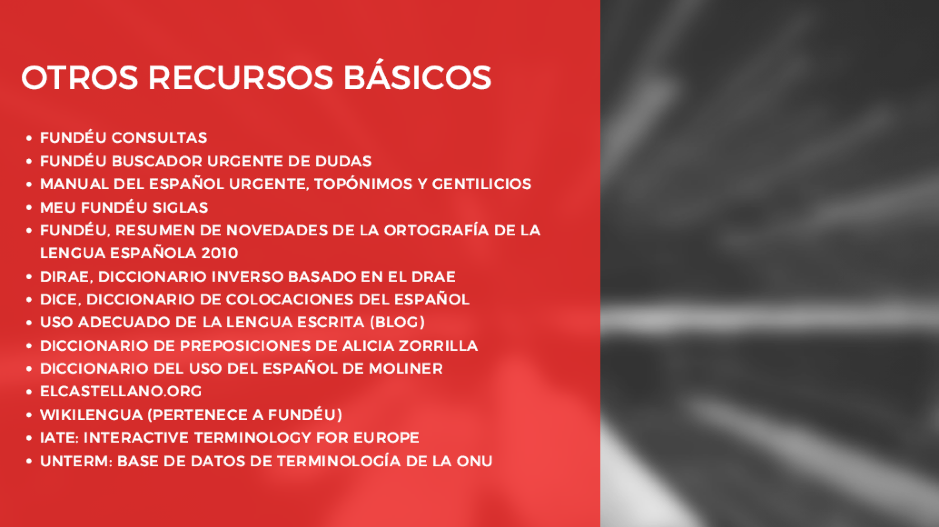

This session by Ana Gabriela González Meade was presented in Spanish and introduced basic tools from the Royal Academy of Spanish and other related resources useful for audiovisual translators. She also shared lots of good tips, showing badly subtitled options and how to fix them.

She first introduced some numbers about the streaming market and went straight into a long list of juicy resources in Spanish, such as the newly introduced RAE platform Enclave (see Figures 8-10).

Figure 8: Main resources in Spanish from RAE

Figure 8: Main resources in Spanish from RAE

Figure 9: Other related resources.

Figure 9: Other related resources.

Figure 10: Enclave platform.

Figure 10: Enclave platform.

In a quick-paced presentation, the speaker went through many common, and usually funny, errors found in dubbing and subtitling, such as false cognates, register mismatches, localisms, syntactic calques and spelling or grammar mistakes, and how to fix them with the above resources. This part provided a plethora of great examples of bad translations and good solutions in Spanish.

At the end, she also listed a few good tips to make the most of our online and offline resources, such as having a quick access to our most heavily used resource, creating your own glossaries, optimizing your Google searches with filters and search operators, including quotation marks, tilde (~), plus or minus signs (+), (-), creating your own list of localisms for languages with many geographical variations, like Spanish, and drafting a document with correct and incorrect options with their corresponding justifications. They were all great strategies for every translator regardless of their specialization.

Lack of Feedback Effect: A Most Effective Audiovisual Translation Training Aid

Ana Gabriela González Meade’s second session was an advanced presentation based on her master’s thesis in audiovisual translation in which she analyzed specific constraints when subtitling audio commentaries in movies. An audio commentary is a separate monologue or dialogue track that accompanies the release of DVD movies, is added to the original soundtrack and includes unscripted commentaries from the movie’s director, cast, writers, producers or critics for the full length of the movie.

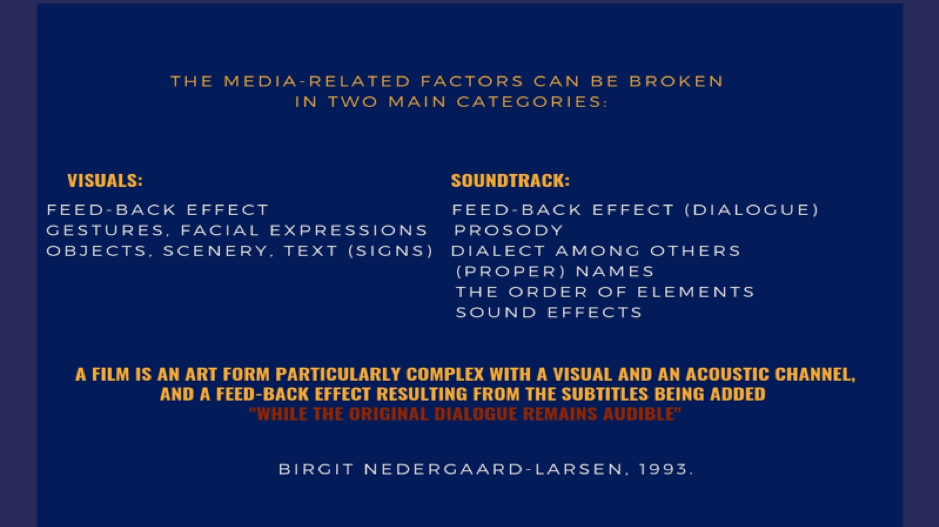

According to Ana Gabriela, up until the arrival of streaming technologies, circa 2013, the arrival of DVD was considered the most widely used format to distribute and market audiovisual content. During this booming DVD industry, she subtitled hundreds of audio commentaries. She quickly went into classifying the types of restraints that characterized her work as a translator of subtitles in audio commentaries. She broke them into two categories: visual and soundtrack constraints (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Visual and audio constraints in audiovisual translation.

Figure 5: Visual and audio constraints in audiovisual translation.

She then introduced the concept of feedback effect, which can be described as the degree to which a target language audience’s knowledge of the source language can interfere or help their comprehension of subtitles. She quoted theorist Panayota Georgakapoulou saying, “the visual information often helps viewers process subtitles, and to a certain extent compensates for the limited verbal information subtitles contain”, but “when important information is not in the images but in the soundtrack, subtitlers should produce the fullest subtitles possible to ensure that the viewers are not left behind.”

Audio commentaries add an additional layer of complexity, says Ana Gabriela. The audience has two original soundtracks to make sense of, that of the original movie with its dialogue and sound effects, and that of the commentator’s monologue. Now an audience in a different language needs to make sense of all this while reading the commentator’s impromptu subtitled monologue. But part of the audio context of this monologue has been lost to both translator and target audience as the original soundtrack is either removed or not subtitled when the commentary is on. Only the visuals remain.

An additional challenge for the translation of audio commentary is its very nature. This is unscripted, casual and sometimes fast dialogue or monologue while the movie is shown in the background. But the translator does not have access to the context of that dialogue, and sometimes the comment does not hold any coherence with what is shown on screen. So subtitlers may need to turn to intonation, voice inflections, and emphasis for coherence and to condensation or omission of repetitions and false starts to comply with reading speed restrictions.

Traducción de subtítulos

Presented by Lina Morales and Kathy Byrd, this was a beginner’s level session in Spanish to any translator who wants to create subtitles for, say a short corporate video, and doesn’t know how or where to even start. The speakers demoed a handful of free or fairly affordable subtitling tools: Inqscribe, Subtitle Horse, SRT Edit Pro, and HandBrake, showing the process from the moment you begin translating or transcribing to syncing the subtitles to the video and burning them to the media.

They introduced the basic format of a subtitle file, called .srt, defined codes as timestamps that show up in videos and used in any subtitle file to sync subtitles to audiovisual content, and presented UTF-8 as the ideal codification format to make sure accents and special characters show correctly on screen.

Lina and Kathy started by demoing Inqsribe, an affordable program that allows transcribing, typing notes, and exporting a subtitle file in an intuitive way ($99, compatible with Windows and Mac). Then they demoed Subtitle Horse, a free online subtitle editor, where they edited subtitles with an .srt file and timecodes with an online video. For those videos you have a file for, like an .mp4, and not a URL, they recommended using SRT Edit Pro ($9.99, only compatible with Mac). They showed how to use SRT Edit Pro to create your own .srt files from scratch and edit an existing one, adjust timecodes and export your final subtitle file.

The final step in the presenters’ workflow was to do a final check using Handbrake to permanently burn the subtitles on the video. Handbrake is a free video transcoder compatible with both Windows and Mac. They advised to make sure to choose the correct encoding format UTF-8 when going through this step to display subtitles correctly on screen.

They also presented an alternative way to edit subtitles already in .srt using Notepad or Word to open the file and edit the text. To make sure you don’t exceed the character limit here, they suggested copying the whole text to an Excel sheet and using the formula =LEN(cell number). This will give you the character count for each subtitle.

Attendees who have never worked on subtitles before left with a very basic, applicable workflow and a taste of what subtitling is like.

Take-aways

The five sessions presented on audiovisual translation at ATA59 provided excellent pointers for beginner and intermediate-level audiovisual translators. By the end, many translators left with applicable toolkits or strategies to try their hand at audiovisual materials or to improve their practice. However, much more education sessions are needed in the future for fairly advanced audiovisual translators and even more is needed for the awareness of audiovisual translation as a new field in translation. We have at least four months until March, the deadline to submit proposals for ATA60 in Palm Springs. Brainstorm ideas and get your proposal ready!